You’ve probably heard the buzz, especially if you’re on social media: eat more protein. Women in perimenopause…eat more protein. Aging adults… eat more protein. Athletes…eat more protein. Want to lose weight? Eat more protein. The marketers have picked up on it because protein is advertised everywhere – protein bars, protein shakes, high-protein foods, labels that scream “high in protein”. But maybe you’re skeptical. After all, haven’t high-protein diets like Atkins come and gone? Is this just another fad, or is there real science behind the hype? And what about the debate on all of those Netflix documentaries, especially from plant-based advocates, who question health benefits of animal protein?

Let’s cut through the noise and explore what science, drawing on insights from experts, tells us about the critical role of protein in managing our health, especially as we age. This isn’t just about building big muscles; it’s about building a foundation for long-term well-being.

Protein and The Rise of Chronic Diseases

Chronic diseases like heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and neurodegenerative disorders are a significant global health challenge, and their prevalence is increasing. It’s estimated that chronic disease kills more than 15 million people each year world wide and 88% of deaths in East Africa are attributed to chronic disease. The same is nearly true for Europeans which is reported that 85% deaths are attributed to chronic disease! While medications are often used to address these issues, they can be expensive, contain synthetic substances, and have side effects. They are often more of a symptom management plan versus a preventative or treatment plan. This has led to a growing interest in alternative approaches, particularly the use of foods, and especially proteins, for managing chronic health concerns.

Dietary patterns, including protein intake, are reported to be a modifying factor in communities with significant prevalence of chronic diseases. The kind and amount of protein consumed have a tremendous impact on the development, prevention, management, and control of diseases. Despite this, protein has often been the “neglected nutrient” in nutrition discussions, which have historically focused more on fat and carbohydrates.

Dr. Donald Layman and colleagues promote a concept called “muscle-centric health” or “protein-centric diets,” emphasizing that maintaining healthy protein turnover is crucial for maintaining healthy body proteins and a healthy metabolism. This perspective views understanding the role of muscle in aging as key to addressing sarcopenia (muscle loss) and living well for a long time.

Protein’s Multifaceted Role in Health Management

While the numbers of chronic disease seem discouraging, there is encouraging news. Protein from food sources offer promising avenues for managing a range of chronic diseases and related health benefits. These include:

- Cardiovascular Diseases (CVD): Managing risk factors like high blood pressure and cholesterol is paramount for individuals with CVD. Lean and plant-based protein sources are typically lower in saturated fats and cholesterol, which helps manage these risk factors. Specific proteins from dairy products have been associated with regulating blood pressure. Protein from fish also offers cardiovascular benefits. In contrast, consuming proteins, especially from red and processed meats, has been associated with a higher chance of colorectal cancer and cardiovascular diseases.

- Diabetes and Glycemic Control: Managing blood sugar levels is a primary concern for individuals with diabetes. Protein can play a crucial role by helping to stabilize blood sugar, having a slower and more sustained effect compared to carbohydrates which can cause rapid spikes. Incorporating lean protein sources like poultry, fish, and beans can help prevent sharp increases in blood sugar after meals, which is essential for maintaining glycemic control. Plant-based proteins, such as those in legumes have also shown promise in enhancing glycemic control.

- Weight Management: High-quality proteins are vital in increasing satiety (satisfying your hunger) and aiding in weight management by influencing appetite-regulating hormones like leptin and ghrelin. When consumed, they increase the release of leptin, which signals sufficient energy reserves to the brain, reducing the drive to eat. In other words, if your body is deprived of protein, it may feel like it’s still hungry causing your appetite to continue to talk at you. Nutrient-dense proteins like lean meats, fish, eggs, and legumes help preserve lean muscle mass during weight loss, essential for maintaining a healthy metabolism. Plant protein foods, through their high fiber content and ability to induce satiety, also contribute to weight management by reducing overall caloric intake.

- Chronic Inflammation and Oxidative Stress: Plant-based proteins, found in legumes, nuts, seeds, and gluten free grains, contain bioactive compounds like polyphenols, flavonoids, and other antioxidants that exhibit anti-inflammatory properties. These properties can potentially reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, key factors in the development and progression of several chronic diseases.

- Muscle Preservation (Especially with Aging): Protein is essential for muscle maintenance and repair, vital for overall health, particularly as people age. Many chronic diseases can lead to muscle wasting or weakness, so adequate protein intake helps maintain muscle mass and strength. As we get older, it becomes harder to build muscle due to anabolic resistance, but it is possible by combining the right type of exercise with the right amount and kind of protein at the right times. Protein metabolism is very different in aging adults compared to growing children. We constantly repair and replace body proteins, needing 250-300 grams of new protein per day, and this process becomes less efficient with aging. Protein and exercise can help improve this efficiency and change the angle of muscle loss associated with aging. Muscle health is highly critical to healthy aging.

- Metabolism: Protein turnover is a very energy-expensive process. While the “calories in, calories out” model is the old story of weight loss, experts argue it’s not the whole story. A high-carb, low-protein diet may not yield the same benefits as adequate protein with less carbohydrate. Excess carbohydrates, especially from starch and sugar, can disrupt muscle function and metabolism and inhibit fat metabolism, leading to higher blood lipids. Experts suggest that excess carbohydrates, rather than fat, drive a lot of the obesity epidemic because they are where we eat excess calories and are often the easiest to change.

Addressing the Adversaries

Concerns about high-protein diets often stem from earlier popular diets. However, the discussion has evolved. The key is not just high protein, but the source, type, and amount of protein, and its balance with other macronutrients. Diet plays a pivotal role in managing chronic diseases, with a particular emphasis on protein intake, but this should be a balanced diet emphasizing whole foods and minimizing processed or red meats where appropriate.

The rise of plant-based diets has fueled debate about protein. Can you get enough protein from plants? Yes, it’s possible to be healthy as a vegan, but it’s tough. Here’s why, according to the sources:

- Protein Quality: Plant proteins are not all created equal. Plants have proteins for their own needs, building roots, seeds, and flowers, which is different from building human brains, hearts, livers, and muscles. While combining beans and grains can provide all essential amino acids, they may not be in the right proportions compared to animal sources.

- The Leucine Factor: A critical challenge for plant-based diets, especially as we age, is getting enough of the amino acid leucine. Leucine is a rate-limiting amino acid for muscle protein synthesis in adults; you need a certain amount at a meal (around 2.5 grams) to effectively turn on the switch to build muscle. Many plant proteins are relatively low in leucine compared to animal proteins like whey.

- Calorie Density: To get the same amount of protein and leucine from many whole plant foods as from animal sources, you often have to consume significantly more calories, particularly from carbohydrates. For example, getting 30 grams of protein might take 4 ounces of chicken (around 270 calories) but two cups of black beans (around 450 calories), which also contain a substantial amount of carbohydrates. Getting sufficient protein (e.g., 120 grams/day) from brown rice alone would require thousands of calories.

- Real-World Intake: National surveys suggest average protein intake for vegetarians in the U.S. is in the mid-60s grams per day, lower than the average adult intake. For those aiming for higher protein levels (e.g., 100-120+ grams/day) or wanting to maximize muscle synthesis, relying solely on whole plant foods is very difficult due to the calorie and carbohydrate load. This is why vegans aiming for high protein often use isolated plant protein powders and potentially added amino acids like leucine synthesized from other sources.

- It Takes Effort: Achieving adequate protein intake, regardless of diet type, requires intentionality and planning.

What about worries that high protein harms kidneys or bones? Concerns about kidneys often stem from diabetes, and while individuals with advanced renal failure may need to adjust protein intake, the research indicates higher protein doesn’t cause the damage. In fact, low protein intake can even shrink kidney size. Concerns about protein causing cancer are also dismissed by many experts.

The Science of “How”: Amount, Timing, and Quality

Based on expert insights, focusing on the amount, timing, and quality of protein is key:

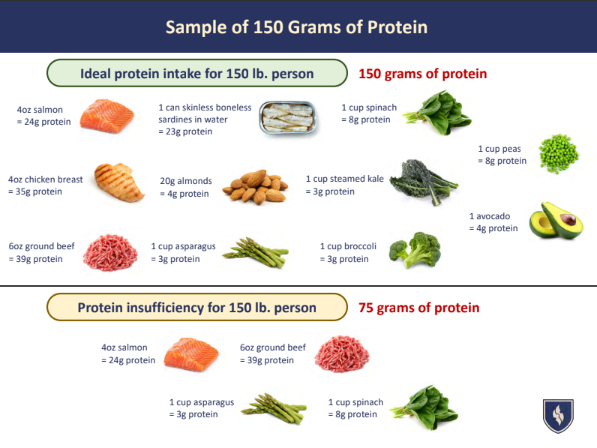

- Amount: The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) of 0.8 grams per kilogram (or 0.36 grams per pound) of body weight is the minimum amount to prevent deficiency, like preventing scurvy with minimal Vitamin C; it’s not necessarily optimal for health or muscle. Experts suggest that aiming for around 0.75 grams of protein per pound of body weight is a better optimal goal for adults (about 1.8 grams per kg). For women, especially midlife women, there’s a threshold around 100 grams per day for metabolic benefits. Unfortunately, many Americans, including 40% of women over 65 and 30% of young women aged 16-26, don’t even meet the minimum RDA. Hitting sufficient protein requires intentionality.

- Timing (Distribution): Where you eat your protein throughout the day matters, especially as you get older. The typical American pattern involves eating the majority of protein (around 65%) late in the day at dinner. This results in a short “anabolic” (muscle-building) period after dinner and a long “catabolic” (muscle-breaking down) period overnight and throughout the day until sufficient protein is consumed. Muscle breaks down overnight to provide amino acids for vital organs. To combat this and maintain muscle, it’s recommended to distribute protein more evenly, prioritizing the first meal after an overnight fast. This first meal helps correct muscle loss observed during fasting. While even distribution (e.g., 30g per meal) is one pattern studied, the key insight is to front-load protein earlier in the day. A goal of 40+ grams of protein in the first meal can be beneficial for satiety and metabolic health, even if it feels like more food than you’re used to. Research on protein intake at the “lunch” meal is surprisingly limited compared to the first and last meals.

- Meal Threshold: To significantly stimulate muscle protein synthesis in adults, there appears to be a minimum threshold of protein needed at a meal. Studies suggest needing around 20-30 grams of protein, specifically about 2.5 grams of leucine, to turn on this process in muscle effectively. Smaller amounts (e.g., 10 grams) may be used by other organs but won’t provide the same stimulus for muscle. Getting 2.5 grams of leucine is roughly equivalent to eating 4-6 ounces of meat, chicken, or fish, or about 20-25 grams of whey protein.

- Quality: As discussed, source matters. Lean animal sources (poultry, fish, eggs, dairy) and plant sources (legumes, nuts, seeds) are recommended. Be mindful that plant proteins may be lower in critical amino acids like leucine and may require higher quantities or supplementation to achieve the same effect as animal proteins. Collagen, despite its popularity, is described by experts in the sourced videos as a “crappy protein” deficient in essential amino acids and likely a waste of money for muscle building.

- Exercise Synergy: Combining protein intake with resistance exercise (even moderate activities like yoga or stretching, which emphasize eccentric motion) has a synergistic effect on improving body composition and muscle health during weight loss and with aging. Exercise actually makes your muscles more sensitive to the amino acids you eat. The timing of protein around exercise might be less critical for well-trained individuals than getting sufficient total protein and distributing it, although consuming protein soon after exhaustive exercise may aid recovery for untrained individuals.

Start Small and Progress

Increasing protein intake and distributing it intentionally can feel daunting, but you can start small:

- Focus on the First Meal: This is often the easiest place to make a big impact. If your usual breakfast is low in protein (e.g., cereal, toast, fruit), aim to add a quality protein source.

- Examples: Add eggs or egg whites, Greek yogurt, cottage cheese, lean meat, or a protein shake to your first meal. Even a handful of nuts or seeds or adding beans can help.

- Aim for a Meal Threshold: Try to get at least 20-30 grams of protein at your first meal and later meals where possible. You can visually estimate (a deck of cards size of meat is roughly 3-4 ounces, providing about 20-28 grams of protein) or use apps to track initially if needed.

- Think Quality Sources: Prioritize lean meats, fish, eggs, dairy, legumes, nuts, and seeds. Reduce consumption of processed and red meats associated with higher risks of chronic diseases.

- Consider Protein Powders: Especially if you’re struggling to hit your protein goals, need to limit calories, have difficulty chewing, or are following a plant-based diet and need concentrated protein/leucine, a protein shake can be a convenient way to boost intake and hit the meal threshold. Whey protein is highly effective for muscle synthesis. Plant-based protein powders (like pea, pumpkin seed, or blends) are also options, particularly those fortified with leucine. (Watch out for unhealthy additives or artificial sweeteners!)

- Don’t Forget Resistance Exercise: Even starting with moderate activities like yoga, resistance bands, or bodyweight exercises a few times a week can significantly enhance the benefits of your protein intake for muscle health.

Achieving optimal protein intake doesn’t happen by accident. It takes planning and intentionality. Start with your first meal and gradually adjust your other meals. Remember, this is about adopting a sustainable dietary pattern, tailored to your individual needs and lifestyle, to support long-term health and manage chronic disease risks effectively. I’m offering a free consultation for anyone interested in preventing chronic disease, increasing your quality of life and aging gracefully. By focusing on science-backed strategies for protein intake and combining it with activity, you can move beyond the trend and build a stronger, healthier future. We can do this together!

Resources:

https://www.metabolictransformation.com/muscle-centric-health-for-healthy-aging

https://www.tommattshow.com/dr-don-layman-the-preeminent-expert-on-protein